Equities: The eyes have it

U-WEN KOK, CFA 22-Jun-2021

Powerful models can prove invaluable for professional investors, but there are limitations to a purely quantitative style when it comes to picking stocks and building portfolios. A hybrid approach—one that includes rigorous fundamental analysis and human oversight of the model—might be the best way to correct for unwanted biases.

We believe this is especially true in the vast world of global equities. Covering the universe of public companies across scores of markets worldwide is seemingly impossible no matter how many “boots on the ground” an investment team boasts. This is where powerful quantitative models can help scan the globe for uncommon opportunities while screening out higher-risk candidates. But as much as we love technology and modeling, it’s clear to us that there must be some human oversight to the investment process to thoroughly vet the model’s output. In other words, trust the model but verify.

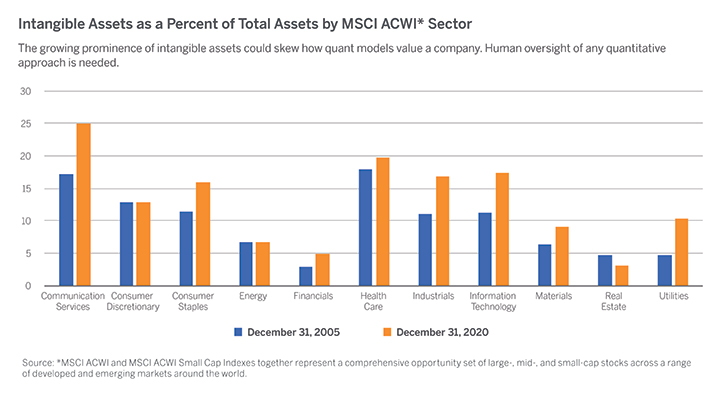

Consider the trend with intangible assets and how they might skew a quantitative investor’s interpretation of company value. Intangible assets are those on and/or off-balance sheet items that have no physical presence, such as goodwill, patents, R&D, brand and even customer relationships. These items have grown significantly as a percentage of total assets over the last 20 years, particularly in sectors such as Healthcare, Technology and Communication Services. In part, this growth reflects expansion in M&A activity and generally greater use of technology and know-how by businesses. Accounting standards have lagged regarding the treatment of intangible assets even though the asset-creating activities of companies have changed and will likely continue to change materially.

Internally created assets (like R&D and brands, for example) are treated as expenses on a firm’s income statement rather than on the balance sheet where they would impact book value. The historical rationale for the expense treatment is that the economic values of such assets were nebulous or even considered speculative, compared to tangible assets (physical plants, machinery, materials, capital, etc). But times change and intangibles, such as intellectual property and data, are much larger drivers of economic value than they used to be. Yet these items remain under-recognized as company assets (until an acquisition occurs) in traditional accounting methods.

All this matter because it skews how a purely quantitative investor might interpret book value and, ultimately, make investment decisions. In fact, while book value to price ratio (“B/P”) remains a widely used quant factor, anecdotally we are seeing quants managers argue that B/P is becoming less important (even meaningless) in their models. Some are removing it altogether. We disagree and contend that B/P remains relevant.

In fact, we see B/P as a factor that offers invaluable insight in some global sectors where tangible assets make up a higher percentage of total assets, such as banks, energy, materials, and real estate. Traditional “value-oriented” industries account for roughly one-quarter of stocks in the MSCI ACWI Index (as of June 2021), but if a global quant manager eliminates or misreads B/P, that manager may also be walking away from some of the most intriguing investment opportunities. This may be especially important today during an early-cycle economic recovery that often sees investors rotating into value-oriented strategies. Moreover, we believe that B/P insight shows low correlation to other broadly employed investment factors, and by retaining B/P as an insight offers added diversification to the models and the resulting portfolios that leverage them.

This is not meant to be a quantitative-bashing exercise. In fact, we contend that a well-diversified investment strategy that leverages both quantitative methods and analyst insights is uniquely poised to capture alpha from B/P (and other factors) over the long term. Our illustration of the evolving nature of intangible assets and how they flow into book value and B/P is but one example of how a model’s output requires the human touch. A purely quantitative approach has its merits, but inputs (and outputs) must be verified, especially when leveraging models to cover the vast universe of global equities.