Is the party over?

WASIF LATIF 21-Jan-2020

As we turn the page into 2020, the fact we are still in the longest running economic and market cycle has no bearing on the its future. There is no definitive expiration date. It’s just not that easy, folks. Perhaps this bull has been running so long because it had so far to recover from the depths of the Global Financial Crisis over a decade ago. Nobody knows for certain.

Yet those who are focused on this “longest-ever” factoid may be missing the key point. Better might be to step back and consider this market within two other historical contexts: valuations and liquidity. Based on that analysis, investors might choose to make some portfolio adjustments.

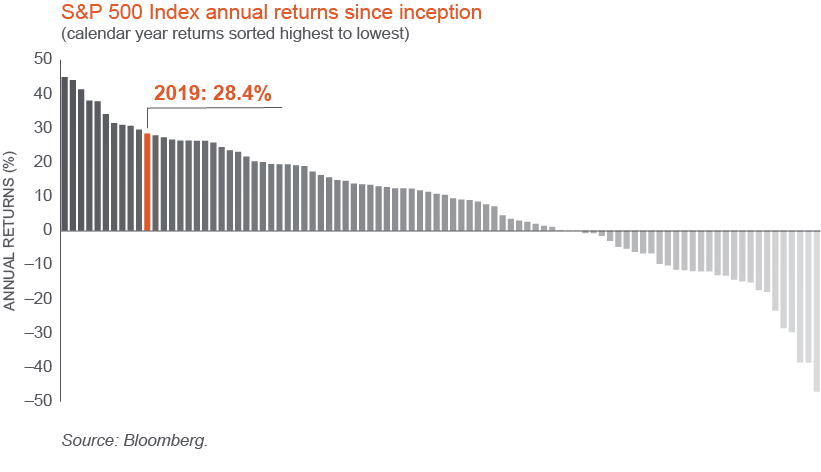

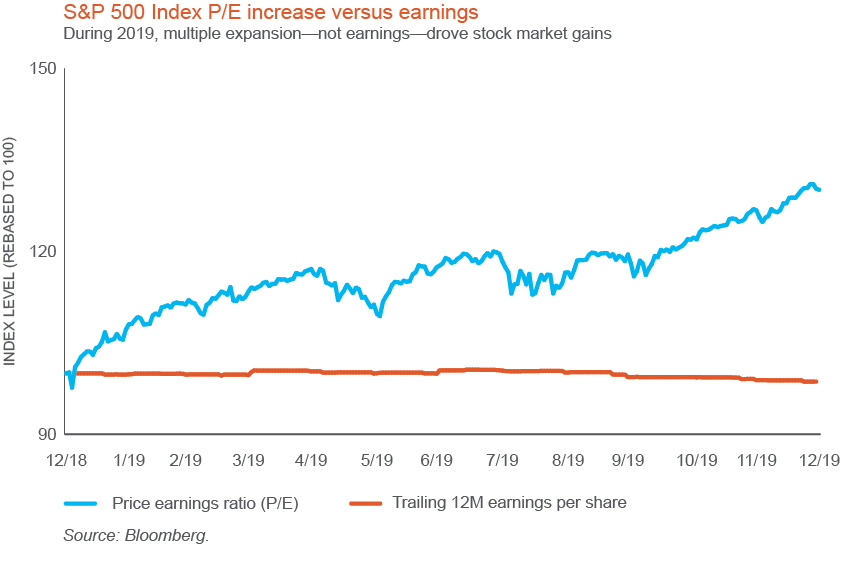

At year end, the S&P 500® Index was approaching its highest valuation level since 1999. While it hasn’t yet matched that historical level just yet, it is indeed in the stratosphere, keeping company with another infamous year, 1929. Moreover, the entire stunning rally in 2019, which represented the eleventh highest calendar-year returns since 1927, was from multiple expansion, not earnings growth.

It is true that the “overvalued” argument is not new and has left many investors in the dust and on the sidelines. Yet we also know what typically happens when market sentiment gets a little too ebullient and concludes that history no longer matter because we’re in a new era of innovation that requires a new way of valuing companies. As Winston Churchill allegedly said: “Those who fail to learn from history are condemned to repeat it.”

History suggests stock valuations are an excellent measures of price performance in the long-term, despite their shortcomings as a near-term indicator. Eventually, investors realize that valuations are ultimately tethered to the fundamentals of corporate earnings’ growth, and this pulls stock prices back towards the mean. That might be up or down, depending on sentiment and where we are in the cycle. So while we acknowledge that valuations are a poor timing tool, valuations matter.

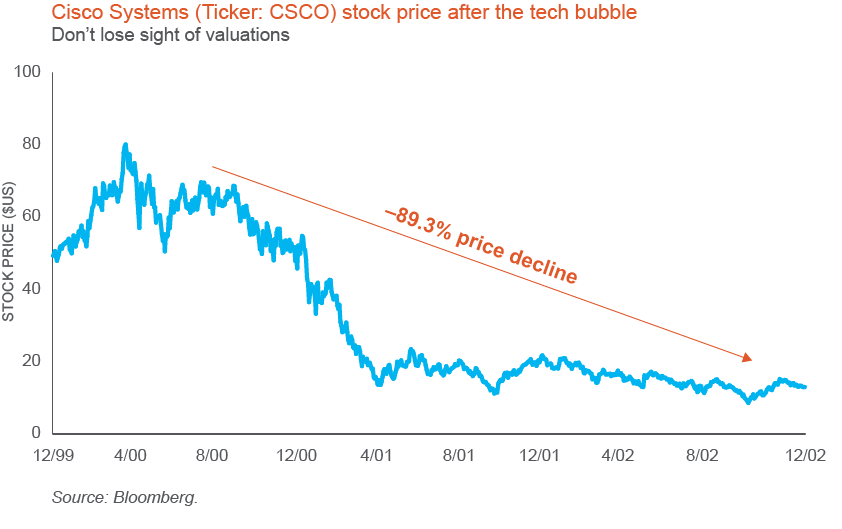

Still, the large-cap tech companies of today are not the dot.coms of yesteryear. Anything but. Many of these tech companies are clear innovators, displacing old incumbents in a range of industries that were ripe for disruption. In fact, many of these tech companies may well deserve their rich valuations and may continue to grow and flourish. But there is a point when even great companies with growing earnings can have a dangerous stock price. That point is not to be underestimated.

Take Cisco¹, a profitable and respected technology stalwart that has been dominant in its space over the long term, as just one example. At the peak of the tech bubble in March of 2000, Cisco had a very rich valuation, illustrated by a 381x P/E. In the ensuing years, Cisco continued to grow and make money while its stock price dropped almost 90%, collapsing the P/E to a still-elevated 26x. CSCO wasn’t necessarily a bad company, but ignoring its valuation back in 2000 was a bad idea.

Liquidity matters

Given the robust market rally of 2019, investors might also wish to question whether the most recent move higher has been fundamentally driven by the underlying earnings growth of companies, or is there something else afoot? The Federal Reserve’s “pivot” to a more accommodative policy just over one year ago certainly was constructive for stocks. And beyond the multiple rate cuts of 2019, The Fed also took some additional unusual steps that may have played a big part in the market rally. Interestingly, this Fed activity also has some historical resemblance.

Back in October 1999, the Fed pumped massive amounts of liquidity into the marketplace to stabilize and ensure the functioning of our financial system—specifically, to smooth any potential hiccups in overnight lending from the Y2K conversion (remember that?). Fast forward to present times. The Fed has once again been providing temporary but extraordinary levels of liquidity to this market, albeit for a completely different set of reasons. Yet investors need to ask whether all this accommodative Fed support was the catalyst that pushed stock prices ever higher in 2019?

These are tough questions, and there is no single definitive answer. And by no means are we perma-bears or doomsayers. But we also believe that history can help us be better investors and that valuations matter in the long run. Given this reality, investors may wish to:

- Avoid brazen market-timing impulses. Rather, maintain an appropriate allocation to equities based on specific risk tolerances and circumstances, but also consider niches that may hold up better in a market prone to turbulence. This might include low-volatility or dividend-paying strategies.

- Reconsider the benefits of traditional passive strategies where performance may be dominated by the largest U.S. companies that coincidentally sport some of the highest historical valuations.

- Determine if reallocating to international and emerging markets equities is appropriate given their current valuations relative to large-cap domestic stocks.